Ebenezer

Scrooge is a significant symbol in Christmas celebrations. When we think about the stingy old humbug, we

know exactly what Christmas isn’t. That

is sad. It completely ignores Scrooge’s story. Our

symbol forgets that Charles Dickens wrote more than a couple of pages about the

old man. We remember Scrooge in chapter

one, but we forget Scrooge’s response to his visitors and thereby we forget

something key. Scrooge is not the villain

of A Christmas Carol. Instead, Scrooge is the confessed – and just

as importantly reformed – villain of A

Christmas Carol. Scrooge demonstrates

that injustice requires a villain and that one way for justice to happen is for

the villain to stop being the villain.

Ebenezer

Scrooge is a significant symbol in Christmas celebrations. When we think about the stingy old humbug, we

know exactly what Christmas isn’t. That

is sad. It completely ignores Scrooge’s story. Our

symbol forgets that Charles Dickens wrote more than a couple of pages about the

old man. We remember Scrooge in chapter

one, but we forget Scrooge’s response to his visitors and thereby we forget

something key. Scrooge is not the villain

of A Christmas Carol. Instead, Scrooge is the confessed – and just

as importantly reformed – villain of A

Christmas Carol. Scrooge demonstrates

that injustice requires a villain and that one way for justice to happen is for

the villain to stop being the villain.

This

essay is best read after reading the novel and will reveal significant plot

points.

Scrooge

is a villain because he is greedy. His

response to people in poorhouses is to neglect charitable donations because he

has to pay taxes. His response to paying

his employee on Christmas Day is to require the clerk to arrive at work early on

Boxing Day. His response to his nephew’s

well wishes is to remind the nephew that he is poor and therefore has no

business saying “Merry Christmas.”

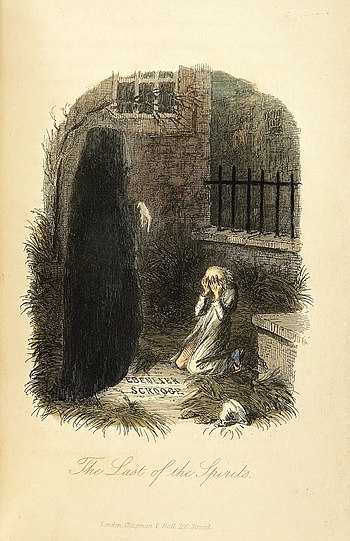

Then

the ghosts come with reminders. The

Ghost of Christmas Past reminds Scrooge that he is greedy because he is afraid

of being poor. The Ghost of Christmas

Present reminds Scrooge that his greed alienates him. The Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come reminds

Scrooge that money has a purpose but Scrooge misused it so people laugh at his

grave.

Other

characters stand in contrast to Scrooge. A poor and physically disabled Tiny Tim does

not wallow in self-pity. He is eager to

go to church on Christmas Eve because he hopes to remind people of Jesus, “who

made lame beggars walk, and blind men see.”

Scrooge’s nephew Frederick, meanwhile, marvels that Scrooge can be so

wealthy and still be so miserable. Frederick

celebrates Christmas, happily singing and feasting around the fire with family

and friends.

The

Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come has an easy job.

The previous two ghosts made their point. Scrooge sits waiting for the ghost and thanks it

for visiting. By the end of the visit,

Scrooge’s repentance is complete. He

cries, “Spirit! Hear me! I am not the

man I was. I will not be the man I must

have been but for this intercourse. Why

show me this, if I am past all hope!”

I

will grant to you that A Christmas Carol

is overly sweet at times but only if you will grant to me that I have met

actual people who are not unlike Tim and Frederick. Sure, the folks I know are real people and are

certainly more complex than the characters of this short book, but they just as

certainly demonstrate that joy is possible amongst people who struggle with

finances or health. The contrast between

the sweet Frederick and Tim and the bitter Scrooge shows readers how

fundamentally Scrooge changes.

A Christmas Carol demonstrates something important

to social justice advocates, especially for Christians who claim a God

that offers forgiveness and repentance.

The ghosts’ purpose was not to shame Scrooge, to defeat Scrooge, or to

destroy Scrooge. Their purpose was to

help Scrooge. The ghosts succeeded not

by demoralizing Scrooge, but by convincing Scrooge of a better way.

My question

after reading Oliver Twist was

whether forgiveness and social justice can co-exist. The answer of A Christmas Carol is clear. Scrooge’s

change stands out, but we cannot forget everyone else who changes as well. The other characters in the book are loving

to each other and to Scrooge (almost unbelievably so), but they still do not

overlook Scrooge’s fault. When Scrooge’s

final ghostly encounter is complete, he rushes out his front door to be part of

the community. The community welcomes

him. Forgiveness and social justice not

only can co-exist, but they must co-exist.

If the people did not forgive Scrooge, justice would not have been

complete. Scrooge would be loving,

giving, and kind but he would be the victim of people who took Scrooge’s love,

gifts, and kindness without reciprocating.

There would be a complete role reversal.

The ghosts would have more people to visit the next Christmas.

There

is a lesson here. What do we want to

happen when we call for social justice?

Do we actually want justice to come?

I’m not always sure we do. I see

this in political debate. We claim that

the opponent is wrong. We give all sorts

of reasons why the opponent is wrong. We

bask in the cheers of the people who agree that the opponent is wrong.

Buy

we do not stop. We give our opponent no

chance to say, “I’ve been persuaded.

Your argument is in fact correct and I now see it your way.” We instead continue to attack the opponent. We instead continue to define ourselves as not

the opponent. We instead accuse the

opponent of flip-flopping if they are persuaded.

Forgiveness

– acknowledging that a positive relationship can exist despite a past grievance

– is then impossible. On the surface at

least, it would seem the only purpose of a good deal of debate is to boost

respective egos. That is not

debate. That is pigheadedness.

(And

it is also arrogant. Notice that the

last three paragraphs assume that I

am correct and the opponent must be

the one to change opinion. Perhaps, but

perhaps also I am not as correct as I expect.

That is a discussion for another post and perhaps another Dickens

novel.)

There

are two questioners in A Christmas Carol. The first is Tim. He chimes, “God bless Us, Every One!” His question is, Do we join this call for blessing when “Every One” includes the

confessed Scrooge? The second is

Scrooge. His question is, If we do not think the villain can reform,

who are we talking to when we call for justice?

These

are important questions as we celebrate the birth of the God who brought

forgiveness.

No comments:

Post a Comment